In Venice, in the fifteenth century, the Republic of Venice is at its peak as territorial expansion, and it is a model and benchmark for the world because of its opening to the religious philosophies, and it is a city ready to welcome all thoughts and trends guaranteeing press freedom.

This is why in that time a large group of “Humanist reformists” comes to Venice, including Aldus Manutius (in 1490), Marco Antonio Sabellico (teacher of rhetoric and author of several works including prayers, writings about topography and Venetian courts) and Francesco Colonna (Dominican friar of the Venetian monastery of Saints John and Paul).

The “Scuola dei stampatori e dei librai” (School of printers and booksellers) met in the Dominican monastery of Saints John and Paul (the present hospital).

On September 18th, 1469, the Senate recognizes that Johann of Speyer (German printer) have introduced and developed the art of printing in Venice, while the “statuto dei Librai e Stampatori” (the statute of the Booksellers and Printers) will be ratified only in 1567.

In 1472 Filippo di Pietro is the first printer properly Venetian (active until 1482).

In 1488 there are almost 200 printing houses in Venice.

One of these is the printing house of Aldus Manutius, not just a typographer but a real publisher (the first in a modern way), who prints 157 titles (even more than a thousand copies with the use of a hand press) between 1495 and 1501.

The environment of his printing house becomes a real literary circle which includes the most outstanding humanists of Italy.

The first studio of the printer is in Calle del Pistor, number 2343, near Campo Sant’Agostin; then he moved onto San Peterniano, near what is now Campo Manin, in 1508.

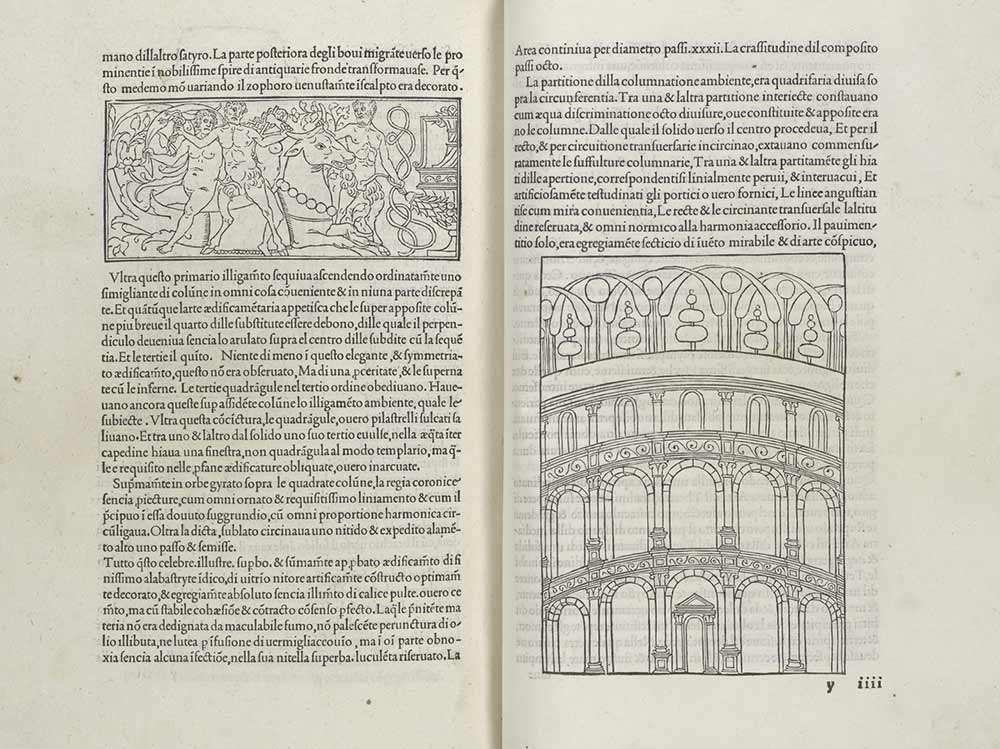

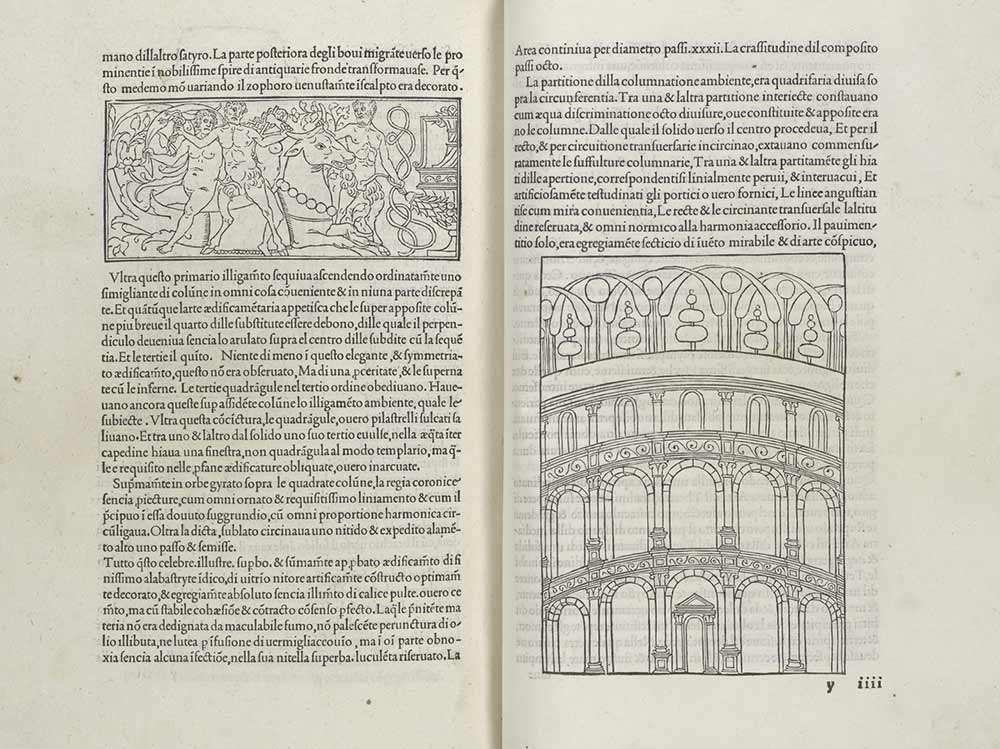

In 1499 Aldus Manutius publishes the ‘Hypnerotomachia Poliphili’, a novel in prose accompanied by 172 xylographs and attributable to the Dominican Francesco Colonna, who is one of the finest books of Italian Humanism.

In 1502 he founded an academy, the “Neacademia dei filelleni” or Aldina, where it was required to speak in ancient greek; those who did not speak ancient greek had to pay a pecuniary fine.

He wants to preserve the literature and the Greek philosophy to further oblivion, along with the great heritage of Latin literature, disseminating the masterpieces in printed editions.

On November 14th, 1502, Aldus Manutius gets from the Senate the prestigious post of Official Printer of the Republic, thanks to his experience, talent and ability. It is unanimously accepted that his trademark (an anchor and a dolphin) refers to the motto “Festina lente” (more haste, less speed) attributed by Suetonius to Octavian Augustus.

Among the most significant contributions of Aldus Manutius to modern typography there is the final version of punctuation, the invention of italics and the beginning of the paperback editions. He was also the first to publish a catalog of his works and he has edited the first book with the pages numbered on both sides.

At the end of the fifteenth century, many engravers in Germany, Holland and Italy reach highest quality results.

The aquaforte etching (engraving on metal plate through the use of acids) was born as an autonomous technique in the early sixteenth century, although the chance to engrave the metal with acids was known since the end of ‘400.

The famous German artist Albrecht Dürer (who begins as a wood designer for woodcuts) was one of the first to use the new aquaforte etching technique- a technique that has probably learned from the Venetian Luca Pacioli (religious, mathematician and italian economist who attended the famous artists of the time ), during his trip to Italy.

Parmigianino (1508-1540) was the first artist to understand the possibilities of the aquaforte etching, using it as a fast means of expression, full of warmth and vitality.

The spread of the aquaforte etching technique frees the artist from the mediation of the artisan, who used to copy his design on wood or on metal plate, mixing together the figure of the artist and the engraver.

Year after year the techniques already existing are improved and new ones are invented, which provide the artists more and more expressive possibilities, as the technique of aquatint (which allows to create veiled painting on the plate, unlike the etching which allows to create lines), perfected by the French artist Jean-Baptiste Le Prince in 1768.

Among the artists who have used this technique we must remember Francisco Goya, who shows the enormous pictorial possibilities of the technical means.

In the Italy of ‘700 should be mentioned artists such as Tiepolo, Canaletto and Piranesi for their high quality works standing apart from the myriad of artisans reproducing works by great masters or detailed views.

In the eighteenth century engraving it became almost exclusively a means to reproduce artworks and portraits and it is brought to a form of industrialization, with the birth of companies that use numerous engravers.

The increasingly refined techniques turn the incision to a mechanistic way, without the beginning vitality and autonomy.

In the late nineteenth century, with the birth and the emergence of photography, the etching with utilitarian and reproductive purposes almost disappears.

From the twentieth century, thanks to artists who come to this ancient discipline with creative spirit, the etching has regained the dignity and freedom of speech that was a characteristic of the beginning of its history.

Madonna dell'Orto

Madonna dell'Orto

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti  Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego

Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego  The Venetian “Fondamenta”

The Venetian “Fondamenta”  2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!

2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!  The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara

The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara