Tag: history

April 25th: St. Mark and the “bocolo”

In Venice on April 25th the feast is one and only one: the feast of St. Mark the Evangelist, patron saint of the city.

Vere da pozzo – Venetian wellheads

Venice is undoubtedly a city unique in all the world, a symphony of treasures, monuments, palaces, glimpses, history, poetry and many other things, and sometimes you are dazzled by all this beauty that you do not realize that just in front of you there are spectacles of architecture, art, and engineering that go almost unnoticed. This is the case of the wellheads (“vere da pozzo” in venetian), real art jewels and above all an expression of the typical venetian wisdom that have contributed to make the Serenissima so powerful.

It may seems strange that a city crossed and surrounded by so much water has always had problems with water supply.

Marin Sanudo, historian and chronicler of Venice, around the early 1500s wrote “Venezia è in acqua et non ha acqua” (“Venice is in the water but has no water”).

Because of its geological shape, the “lidi” (shores) were the only areas where rich water sources were present and where they found natural wells, formed by the accumulation of rainwater filtered and depurated by the sand.

Finding these wells could have influenced the method of construction of the wells, because only Venice used layers of sand to filter and make rainwater drinkable.

Since the Middle Ages, citizens began to build underground cisterns, while the government encouraged and promoted the construction of water systems.

The solution to the water problems of an ever-growing population was finally found thanks to the realization of the “Venetian wellheads“.

Photo by Wolfgang Moroder

These structures served both as a freshwater cistern -the freswater was carried by the Brenta and Sile rivers (task of the “Corporazione degli Acquaioli” founded in 1386)- and for the purification of rainwater.

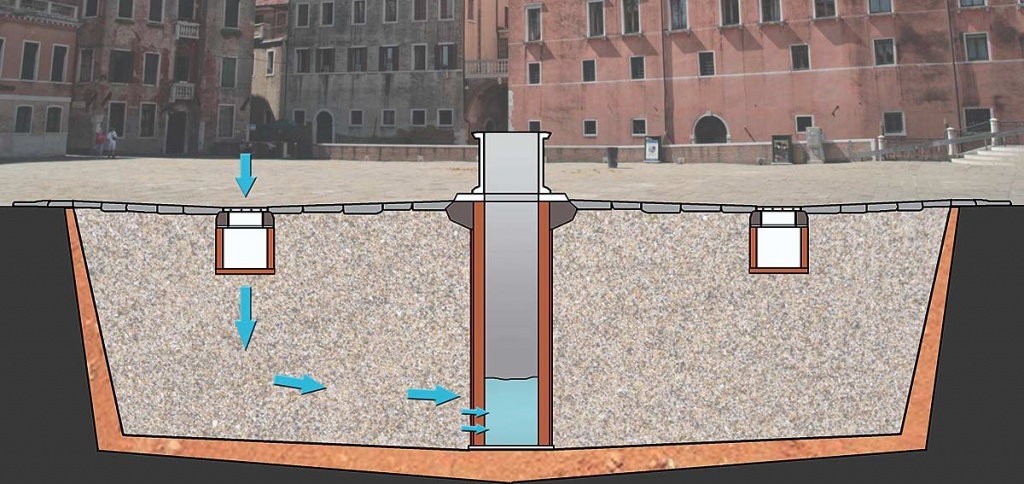

Once found the best place for the well, they began to dig (usually no more deep than 5 meters below the sea level) sometimes raising an entire “campo” (field) to reach the required depth and to avoid that the brackish water of the lagoon enters the cistern as a result of the rising tide.

The walls and the bottom of the underground cistern were covered with a layer of clay that made it impermeable to any brackish water infiltration from the ground.

The clay was then covered with layers of clean sand of different sizes, which was constantly wet, and which had the aim to filter the rainwater.

Rainwater was collected inside the well through two or four stone blocks of Istria, called “pilelle”, arranged symmetrically in relation to the well barrel.

In some wells, the perimeter of the underlying cistern was visible on the surface thanks to a frame of Istrian stone.

Underneath the “pilelle”, they build structures made of bricks shaped like bells open at the bottom to convey as much water as possible, while the above pavement was slightly elevated around the mounds to help the water to drain thanks to the gravity.

At the bottom of the cistern, just at the center of the excavation, they placed a slab made of stone of Istria on which they built the well barrel with special bricks, called “pozzali”, which allowed the filtered rainwater to enter the barrel.

At the top of the barrel, usually above one or two steps, they placed the “vera da pozzo” (wellhead), the only part of the structure external to the pavement.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org // Author: Marrabbio2

Usually the venetian wellheads were made of Istrian stone and Veronese limestone, though sometimes the oldest wells were obtained from large capitals coming from Roman buildings.

Over time, and with the evolution of architectural taste, the wellheads became ornamental elements, with many different shapes and decorations.

Building a wellhead was a very expensive and demanding hard work due to the complexity of the proceedings, and the Republic encouraged the richest families to donate a well to the city, thus bringing prestige to the family. This is why you can see a lot of wellheads with aristocratic coat-of-arms, inscriptions and bas-reliefs of the families that took charge of the construction.

The placing of the wellheads could be very different: from the public “campi” (fields) to the private courtyards or cloisters.

Maintenance was necessary to keep the well in order and healthy, and it was just the Republic that took care of this, assuring that infantrymen of the “Provveditori alla Acque” supervised the wellheads.

Parish priests and county leaders had to check wells too: these had the keys of the cisterns, which were opened twice a day (morning and evening) to the sound of the “campana dei pozzi” (bell of the wells).

According to a statistics compiled by the Municipal Technical Office on December 1st, 1858, there were 6046 private wells, 180 public wells, and 556 basement wells.

In the 19th century, after the construction of the city aqueduct, the use of the wells was progressively abandoned and the wells were closed to the top with metal or cement cover for security reasons.

Today there are 600 wellheads and they fulfil a purely aesthetic function, in a city that in the past has always been able to improve through difficulties thanks to the intelligence and the willingness of its inhabitants.

Sources

A. Penso, I Pozzi, in ArcheoVenezia del 4 dicembre 1995

http://venezia.myblog.it/2016/01/20/le-vere-pozzo-venezia-straordinario-sistema-idrico-ornamento-della-serenissima/

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pozzo_(Venezia)

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vera_da_pozzo

http://veredapozzo.com

https://venicewiki.org/wiki/Vere_da_pozzo

The Redentore Feast in Venice

The Redentore Feast (Redeemer’s Feast) is a traditional feast of Venice: it is celebrated on the third Sunday of July and it is certainly deeply felt by the Venetians.

The Saturday before the third Sunday of July a long votive bridge of boats is opened on the Giudecca Canal connecting the island with the Zattere, thus allowing people to reach the Redentore Church.

The Redeemer’s Day is the event that celebrates the building of the Redentore Church by order of the Venetian Senate in 1576 as an ex-vote for the liberation of the city from the plague of 1575. The terrible plague caused the death of more than 50,000 people in just two years.

At the end of the plague, in July 1577, it was decided to celebrate every year the liberation from the plague with a votive deck being set up.

This celebration has become over time a tradition very much felt by the Venetians and it is still very much alive – and it is very healthy, indeed – after almost five centuries.

The festival is famous (also called “la notte famosissima – the very famous night”) especially for the wonderful fireworks show (“i foghi – the fires”) that takes place the night between Saturday and Sunday on the San Marco basin, which for the occasion is closed to normal navigation and welcomes the boats of the many Venetians who pour into the dock to eat, drink, dance and spend a night together.

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti  Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego

Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego  The Venetian “Fondamenta”

The Venetian “Fondamenta”  2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!

2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!  The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara

The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara