Tag: venice history

April 25th: St. Mark and the “bocolo”

In Venice on April 25th the feast is one and only one: the feast of St. Mark the Evangelist, patron saint of the city.

The birth of Venice

On 25 March Venice celebrates its birthday.

According to Martino Da Canal in his “History of Venice” the date of birth of the city is March 25, 421. The date coincides with the consecration of the church of San Giacometto on the banks of the current Grand Canal, which marks the first settlement in Venice on the Riva Alta (Rialto) according to the 11th century Chronicon Altinate.

Actually, the most beautiful city in the world does not have a precise date of birth, but it is the result of continuous movement and change.

Going back in time we would not have seen any expanse of uncontaminated water, as we could imagine looking at the lagoon, with its sandbanks, its islets and its peace.

What we could have seen was the dominance of the continent in the eternal struggle between land and sea.

The Alpine rivers, flowing into today’s lagoon, continuously carried debris that created an expanse of land covered with forests, interspersed with freshwater marshes and a few brief hillocks (“dosso” in italian, dossum durum which will give its name to Dorsoduro, one of the districts of Venice, and dossum oliveti, which will give its name to Olivolo, today’s Castello, another district of Venice).

A freshwater stream, the rivus altus (Rialto), marked the current course of the Grand Canal, on whose banks human settlements had been built since prehistoric times, as well as in the territory of Torcello.

In the basin of San Marco stood a saltern, with the floor in Roman bricks placed more than 3 meters below the current level of the common tide.

According to Titus Livius, the fugitives from the Trojan War came in search of refuge on the Venetian coast and Aeneas founded Venice in 1107 BC. Martino da Canal also describes how the Trojans landed in the area of Olivolo and placed there their first settlement.

One of the first centers built was a port called Metamauco and dates back to Roman times. It stood near today’s Malamocco, in the Lido of Venice, and was located at the mouth of the river Medoacus Maior, the current river Brenta.

Legend has it that it was located further out to sea than the modern Malamocco. A catastrophic climatic event caused it to sink under the sea and it is said that in good weather you can still see its submerged walls and that the fishermen’s nets sometimes remain imprisoned in the tip of the bell tower.

During the last two millennia the activity of tides, winds, coastal currents and the progressive rise in sea level led to a gradual transformation from continent to lagoon, accentuated by the deviation of rivers led to flow into other parts of the coast by man.

Venice begins to see its population grow as a result of the barbarian invasions that followed one another since the fifth century. The fugitives found in the lagoon city protection provided by the Byzantine Empire, present in the territory in different administrative forms.

The growing economic development and the distance from the capital Constantinople were the circumstances that allowed to achieve the administrative autonomy that led to the birth of the Republic of Venice, the Serenissima.

In a short time Venice conquered the political and military hegemony in the Adriatic Sea and throughout the Mediterranean, becoming the main seaport and trading center.

Immediately afterwards, the Serenissima will reach its maximum splendour.

“And if their lagunes are gradually filling up, if unwholesome vapours are floating over the marsh, if their trade is declining, and their power has sunk, still the great place and the essential character will not, for a moment, be less venerable to the observer.”

– Johann Wolfgang Goethe

Sources

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storia_di_Venezia

http://www.viagginellastoria.it/archeoletture/luoghi/1940venezia.htm

https://evenice.it/blog/info/compleanno-di-venezia.html

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martino_Canal

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storia_della_Repubblica_di_Venezia

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repubblica_di_Venezia

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti

In Venice there are no streets but calli (with a few exceptions, as we learned here), and it’s just the same for the squares: if you hear about “square”, you can’t help to refer to St. Mark’s Square, the one and only square in Venice.

All the other areas of the road network that in the rest of the world are called squares, in Venice are called Campi (Fields).

On ancient times the campi, as the term suggests, were covered with grass and used for cultivation, with orchards and fruit trees, and sheeps or horses could be found grazing there.

Only recently the campi have been paved, but there is still a testimony of what the fields should look like on the days of the Serenissima: to see it just visit the Campo di San Pietro di Castello, with its meadows and trees.

San Pietro di Castello

The social meaning of the campo has always been very strong, since Venice is a polycentric city, built on numerous islands that lived a life of their own.

The open space surrounded by houses was a meeting place for the inhabitants, a place where there was a market and overlooked the craft shops.

On the campo there was always a church, with an adjoining cemetery; the function of the campo as a burial place is still indicated in some cases with the presence of an elevated area more than a meter above normal traffic (Napoleon then banned the practice of burial in the campi, moving the cemetery to the current island of San Michele).

Campo San Trovato and the former cemetery

In the larger campi there were also processions and religious events, as well as tournaments and public speeches.

Even in much more recent times, the campo has been (and still is, even if the depopulation of Venice dramatically has its strong impact) the meeting place of children who played mainly football or other games, such as jumping the rope or going on skates.

Campo dei Gesuiti with children playing football

The well was another inevitable figure in every campo, and it was the only source of water for the city, before the construction of the aqueduct.

Fortunately you can still admire many real finely worked wells, even if unused (if you want to learn more about the functioning of the wells, read this article).

The campi often owe their name to the churches that rise (or rised) there, but also to important families who lived there or to trades that were carried out in ancient times.

When the campo is smaller than usual it is referred to it as Campiello (small field), which is often only a widening of the calle or an appendix to a larger field, and it is usually devoid of well and surrounded by houses.

In the campiello social life was even more typical, because it was just the center of a micro district, where the social fabric of the city was interwoven, with gossip, quarrels and the popular chatter of a lively and crowded city. Carlo Goldoni in his comedy “Il campiello” tells just these habits.The importance of the campiello is also testified by the name given to the important literary prize “Il campiello”, one of the most prestigious and well-known Italian literary prizes.

Campiello

Even smaller than the campiello is the Corte (courtyard), which usually has only one entrance through a portico or a street sometimes equipped with a gate. In fact, the corte was considered an extension of the house, where you could find women who, during the summer, sitting next to their door, engaged in housework activities such as cleaning fish and vegetables, sewing and embroidery, and the practice of inserting beads into a thread for the manufacture of necklaces, a typical activity that in dialect is called “impiraperle”.

Corte

Sources

https://venicewiki.org/wiki/Campo

https://www.innvenice.com/Toponomastica-Venezia.htm

https://venipedia.it/it/campi

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campo_(Venezia)

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campiello

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corte_(Venezia)

Vere da pozzo – Venetian wellheads

Venice is undoubtedly a city unique in all the world, a symphony of treasures, monuments, palaces, glimpses, history, poetry and many other things, and sometimes you are dazzled by all this beauty that you do not realize that just in front of you there are spectacles of architecture, art, and engineering that go almost unnoticed. This is the case of the wellheads (“vere da pozzo” in venetian), real art jewels and above all an expression of the typical venetian wisdom that have contributed to make the Serenissima so powerful.

It may seems strange that a city crossed and surrounded by so much water has always had problems with water supply.

Marin Sanudo, historian and chronicler of Venice, around the early 1500s wrote “Venezia è in acqua et non ha acqua” (“Venice is in the water but has no water”).

Because of its geological shape, the “lidi” (shores) were the only areas where rich water sources were present and where they found natural wells, formed by the accumulation of rainwater filtered and depurated by the sand.

Finding these wells could have influenced the method of construction of the wells, because only Venice used layers of sand to filter and make rainwater drinkable.

Since the Middle Ages, citizens began to build underground cisterns, while the government encouraged and promoted the construction of water systems.

The solution to the water problems of an ever-growing population was finally found thanks to the realization of the “Venetian wellheads“.

Photo by Wolfgang Moroder

These structures served both as a freshwater cistern -the freswater was carried by the Brenta and Sile rivers (task of the “Corporazione degli Acquaioli” founded in 1386)- and for the purification of rainwater.

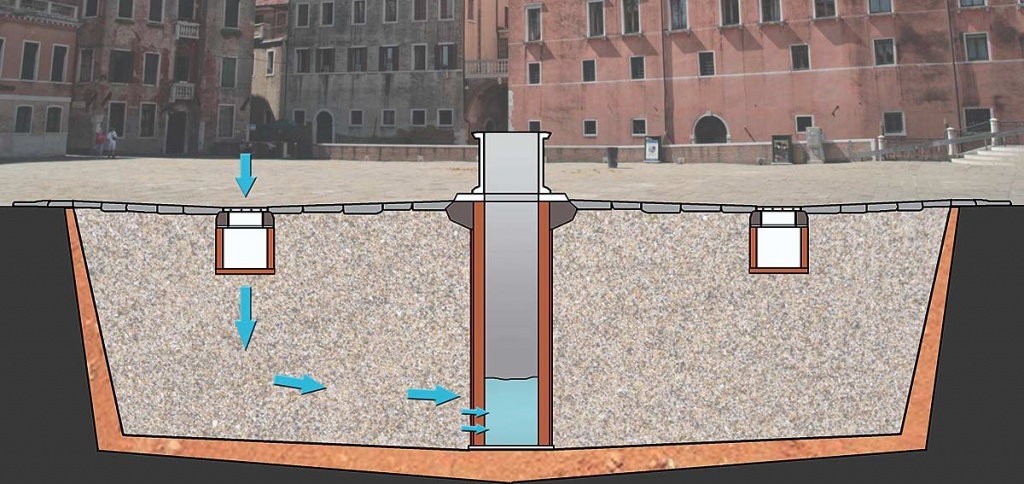

Once found the best place for the well, they began to dig (usually no more deep than 5 meters below the sea level) sometimes raising an entire “campo” (field) to reach the required depth and to avoid that the brackish water of the lagoon enters the cistern as a result of the rising tide.

The walls and the bottom of the underground cistern were covered with a layer of clay that made it impermeable to any brackish water infiltration from the ground.

The clay was then covered with layers of clean sand of different sizes, which was constantly wet, and which had the aim to filter the rainwater.

Rainwater was collected inside the well through two or four stone blocks of Istria, called “pilelle”, arranged symmetrically in relation to the well barrel.

In some wells, the perimeter of the underlying cistern was visible on the surface thanks to a frame of Istrian stone.

Underneath the “pilelle”, they build structures made of bricks shaped like bells open at the bottom to convey as much water as possible, while the above pavement was slightly elevated around the mounds to help the water to drain thanks to the gravity.

At the bottom of the cistern, just at the center of the excavation, they placed a slab made of stone of Istria on which they built the well barrel with special bricks, called “pozzali”, which allowed the filtered rainwater to enter the barrel.

At the top of the barrel, usually above one or two steps, they placed the “vera da pozzo” (wellhead), the only part of the structure external to the pavement.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org // Author: Marrabbio2

Usually the venetian wellheads were made of Istrian stone and Veronese limestone, though sometimes the oldest wells were obtained from large capitals coming from Roman buildings.

Over time, and with the evolution of architectural taste, the wellheads became ornamental elements, with many different shapes and decorations.

Building a wellhead was a very expensive and demanding hard work due to the complexity of the proceedings, and the Republic encouraged the richest families to donate a well to the city, thus bringing prestige to the family. This is why you can see a lot of wellheads with aristocratic coat-of-arms, inscriptions and bas-reliefs of the families that took charge of the construction.

The placing of the wellheads could be very different: from the public “campi” (fields) to the private courtyards or cloisters.

Maintenance was necessary to keep the well in order and healthy, and it was just the Republic that took care of this, assuring that infantrymen of the “Provveditori alla Acque” supervised the wellheads.

Parish priests and county leaders had to check wells too: these had the keys of the cisterns, which were opened twice a day (morning and evening) to the sound of the “campana dei pozzi” (bell of the wells).

According to a statistics compiled by the Municipal Technical Office on December 1st, 1858, there were 6046 private wells, 180 public wells, and 556 basement wells.

In the 19th century, after the construction of the city aqueduct, the use of the wells was progressively abandoned and the wells were closed to the top with metal or cement cover for security reasons.

Today there are 600 wellheads and they fulfil a purely aesthetic function, in a city that in the past has always been able to improve through difficulties thanks to the intelligence and the willingness of its inhabitants.

Sources

A. Penso, I Pozzi, in ArcheoVenezia del 4 dicembre 1995

http://venezia.myblog.it/2016/01/20/le-vere-pozzo-venezia-straordinario-sistema-idrico-ornamento-della-serenissima/

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pozzo_(Venezia)

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vera_da_pozzo

http://veredapozzo.com

https://venicewiki.org/wiki/Vere_da_pozzo

The Venice Historical Regatta and Caterina Cornaro: the strength of a woman

The Venice Historical Regatta will take place on Sunday, September 3rd, (the Regata takes place the first Sunday of September) and it will have its climax in the beautiful “gondolini” racing, a fascinating race, rich in tradition and historic rivalries as well.

Before the official races, there will be a beautiful historical parade which recalls a particular episode of Serenissima’s history: the triumphant return of Caterina Cornaro from Cyprus to Venice in 1489.

Who was Caterina Cornaro, and why is this recurrence celebrated? What’s her story?

Caterina’s story is in fact the story of a strong, courageous and beloved woman which mixes strong feelings and political intrigues.

Caterina Cornaro (in Venetian the second name is “Corner”) belongs to one of the most powerful Venetian families. She was born on November 25th, 1454 in Venice and spent her early childhood in the family palace on the Grand Canal and later in a monastery near Padua.

At 14, she married Giacomo II of Lusignano by proxy, king of Cyprus and Armenia. The wedding was proposed by her uncle Andrea Corner, exiled from Venice to the island of Cyprus.

Needless to say that it was the classic marriage of convenience, and in this case there were many good reasons: the Cornero could better manage their possessions in the island, Venice could extend its influence on Cyprus and thus consolidate its control on the Mediterranean Sea, and finally Cyprus found thus a powerful ally in the struggle against Genoa, who yearned for Famagusta, and against the Turkish.

Actually, Giacomo II delayed his marriage commitment because he tried to approach the Kingdom of Naples, enemy of Venice; however, the insistence of the Venetians and, above all, the Ottoman advance convinced him to respect the treaties and in 1469 he concluded an alliance that guaranteed Cyprus under the protection of the Republic.

That’s how in 1472, when she was 18, Caterina left Venice on board of the Bucintoro to arrive in her new residence in Nicosia, where she got married and she was crowned queen.

Less than a year later, in July, Giacomo suddenly died, leaving Caterina pregnant of their son, Giacomo III, who would be born the following month.

Meanwhile the queen was excluded from the throne which was entrusted to a college of “commissars”. It was very difficult for Caterina to succeed in being recognized as Queen of Cyprus, but she resisted and remained until the Venetian fleet reached the island and restored order.

From March 28th, 1474, the Republic of Venice affixed to Catherine a commissioner and two counselors, removing some of the queen’s trusted men from the island.

Catherine, however, was a lonely woman, and the premature death of little Giacomo III made her increase her loneliness so much that she fell into depression. She was thus achieved by her father who helped her to overcome her illness and to improve her relationships with Venice, obtaining more freedom.

There were two conspiracies by noble Catalans who tried to overthrow the reign of Caterina, both repressed by the Republic of Venice.

After the second attempt, the Serenissima began to press for Caterina to return home and to surrender the kingdom to Venice in exchange for benefits worthy of a queen.

Caterina did not accept, but finally she had to surrender because of the intercession of his brother Giorgio Cornaro: on February 26th, 1489, dressed in black, she had to relentlessly leave the island forever and to return home, giving the island to Venice.

On June 6th, 1489, sitting on the Bucintoro next to Doge Agostino Barbarigo, Caterina made her triumphal entrance to Venice, which received her “daughter” with great affection: she was named “domina Aceli” (Lady of Asolo), retaining her title and rank of queen.

The historical parade of the Regata recalls just this episode: the embrace of the city to a strong and unlucky woman, who has always kept its integrity and dignity exemplarily.

During the reign of Caterina, Asolo’s court became famous for welcoming famous artists and literati. However, her life in the castle of Asolo was no less tormented: in 1509 she had to flee twice because of the advance of the Hapsburg troops, taking refuge in Venice, her city, where she died in 1510.

They say that the crowd who wanted to participate to the funeral was so big that they had to build a bridge of boats from Rialto to Santa Sofia to allow a better outflow.

Caterina still rests in the church of San Salvador, near Rialto Bridge.

Madonna dell'Orto

Madonna dell'Orto

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti  Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego

Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego  The Venetian “Fondamenta”

The Venetian “Fondamenta”  2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!

2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!  The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara

The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara