Only three days to the 43rd edition of the Vogalonga here in Venice!

Vogalonga is a rowing regatta in the Italian city of Venice.

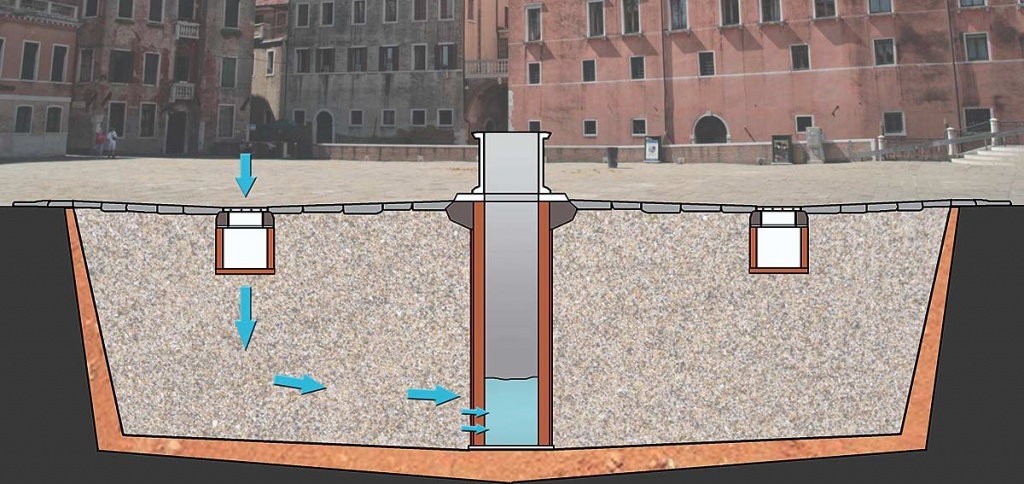

On November 11th, 1974 a group of Venetians, both amateur and professional rowers, had a race. They came up with an idea of non-competitive “race” in which any kind of rowing boat could participate, in the spirit of historical festivities. The first Vogalonga began the next year with the message to protest against the growing use of powerboats in Venice and the swell damage they do to the historic city.

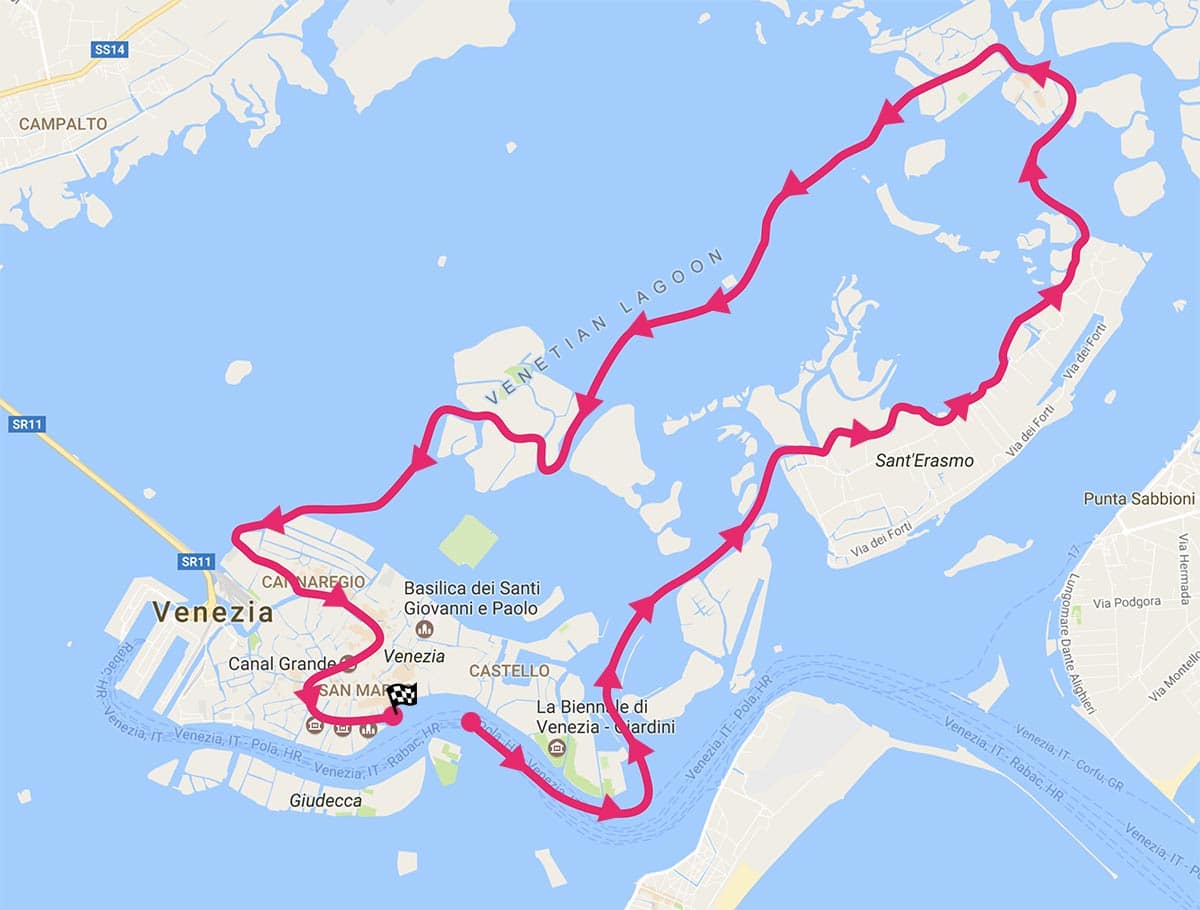

Participants gather in St Marks Basin in front of the ducal palace. The racecourse is scenic route 30 kilometers long along the various Venetian canals and historical buildings, and reach islands like Sant’Erasmo, Burano and Murano.

The route of the Vogalonga

At the this first edition there were about 1.500 riders.

The following editions Vogalonga gradually increased consensus and participation, reaching over 8,000 members this year (absolute record), with regattas coming from around the world and with all kinds of rowing boats.

Each participant receives a commemorative medal and a certificate of participation.

Thanks to www.vogalonga.com

boats at the start of Vogalonga

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti  Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego

Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego  The Venetian “Fondamenta”

The Venetian “Fondamenta”  2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!

2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!  The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara

The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara