The celebration of the carnival derives from very ancient festivities, such as the Greek Dionysian and Roman saturnalians, when for a limited period of time social obligations and hierarchies disappeared.

From a religious and historical point of view the carnival represented a moment of symbolic renewal of the social order through the chaos during a limited period.

Like the Roman Empire, also the Serenissima in Venice needed to give vent to its population: with the use of masks and costumes there was a levelling of social classes and sexes, where anyone could be something different from himself.

Anonymity made the people free, giving them an outlet from tensions and bad moods.

Since it is linked to the celebration of Easter, Carnival does not have a fixed date, although the main part of the festivities is concentrated between Fat Thursday and the following Mardi Gras which marks its end, with the beginning of Lent.

The Carnival in Venice has very ancient origins, with its first testimony in a document of the Doge Vitale Falier in 1094, where it talks about public entertainment: the Senate of the Republic will officially declare that the Carnival of Venice is a public holiday in an edict of 1296.

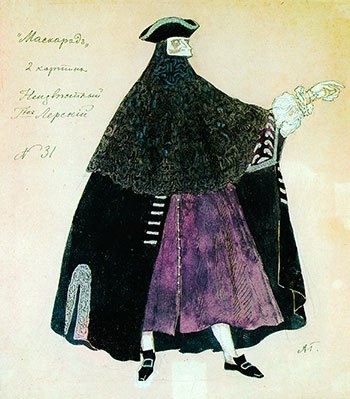

With the use of fundamental disguises, a new trade was born in Venice, the trade of masks and costumes, since 1271. The freedom of anonymity during the Carnival, however, gave the possibility of committing crimes of different nature, so much so that in 1339 a decree forbade to circulate masked during the night.

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti  Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego

Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego  The Venetian “Fondamenta”

The Venetian “Fondamenta”  2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!

2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!  The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara

The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara