Tag: Venice

The Carnival of Venice

The celebration of the carnival derives from very ancient festivities, such as the Greek Dionysian and Roman saturnalians, when for a limited period of time social obligations and hierarchies disappeared.

High water in Venice: we try to do some clarity

A small introduction: I’m writing this article not to refresh notions studied during geography classes at the primary school, but just to give truthful information about the situation here in Venice after the high waters.

After the disastrous tides of last November and the less traumatic but nonetheless problematic ones of December, articles and news have circulated that have created a climate of terror among those who wanted to come and see the most beautiful city in the world in person, leading to the mass cancellation of a considerable portion of future visitors.

If you ask a Venetian the question: “What about the water?” the answer you will most likely get will be: “Six hours grows, six hours falls.”

The relationship of the Venetians with the lagoon and its tides is something that has lasted for hundreds of years, and it is as natural as breathing in a living body.

Piazza San Marco allagata, Vincernzo Chilone, 1825

Not so simple (of course) is for the tourist to understand this simple truth: no matter how the tide may rise, no matter how much damage and disasters, inconvenience and loss it may bring, it will ALWAYS decrease. In the worst case you can have two high tides with a low tide in the middle not very low, which can lead to have high water for a whole day, but in exceptional cases: after its time the water will naturally flow back to the sea.

Even in the case of the exceptional tide of November, 13th (187 cm above sea level), when the water reached its maximum, (I must say that it was a really considerable maximum, in the shop I had 60 cm of water inside and a small fish swimming) the tide began to flow out quite quickly, so that in a few hours it had completely disappeared from the streets.

In general anyway the tide is a good thing, it circulates water inside the lagoon and brings life, like blood inside the veins. It may happen that at certain times there is the possibility of water rising, and even a lot as we have seen, but it will always be a TEMPORARY situation.

High tides are a seasonal phenomenon, often occurring in November and December: don’t be afraid of the tide, like the Venetians who have always lived with it- the water won’t hurt you or drown you (don’t fall into the canal though!). All you need is a pair of rubber boots and you can almost always get around the city without too much trouble and enjoy an unusual view.

In case you are in Venice during an exceptional tide you will find a sheltered place or stay in your hotel room for a few hours, in the heat and shelter you will not suffer great privations, with running water and electricity you will not even notice what is happening outside.

As for the boots, please don’t buy the disposable ones sold by street vendors or peddlers, they don’t last long for what they cost and risk leaving you with your feet soaking when you least expect it, and often the temptation to leave them where they happen is strong (not to mention the garbage bags that many people use as ephemeral protection).

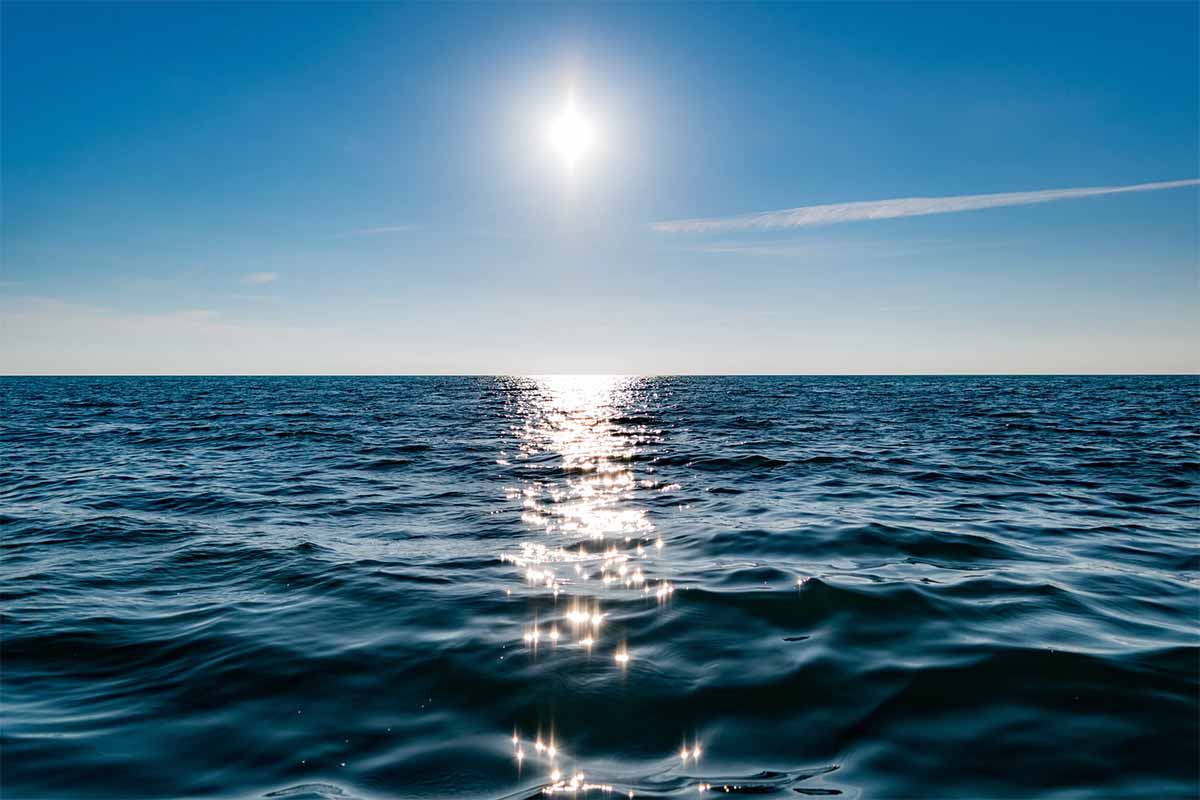

Keep in mind that everything you leave ashore during a high tide will be dragged into the canals by the runoff of the water. From there it will reach the lagoon and then the sea, and in the sea it will travel for decades (hundreds of years?) without anyone taking care of removing it, polluting forever the sea that is ours and yours and that we continue to love in all its forms, even after it has taken so much from us because of its most violent phenomena.

Come to Venice without any worries, you won’t regret it.

Venice hasn’t sunk yet!

San Giovanni e Paolo Civil hospital

The San Giovanni e Paolo Civil hospital was previous known as Scuola Grande di San Marco, which is a Renaissance building located in Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo, in Castello district.

April 25th: St. Mark and the “bocolo”

In Venice on April 25th the feast is one and only one: the feast of St. Mark the Evangelist, patron saint of the city.

The birth of Venice

On 25 March Venice celebrates its birthday.

According to Martino Da Canal in his “History of Venice” the date of birth of the city is March 25, 421. The date coincides with the consecration of the church of San Giacometto on the banks of the current Grand Canal, which marks the first settlement in Venice on the Riva Alta (Rialto) according to the 11th century Chronicon Altinate.

Actually, the most beautiful city in the world does not have a precise date of birth, but it is the result of continuous movement and change.

Going back in time we would not have seen any expanse of uncontaminated water, as we could imagine looking at the lagoon, with its sandbanks, its islets and its peace.

What we could have seen was the dominance of the continent in the eternal struggle between land and sea.

The Alpine rivers, flowing into today’s lagoon, continuously carried debris that created an expanse of land covered with forests, interspersed with freshwater marshes and a few brief hillocks (“dosso” in italian, dossum durum which will give its name to Dorsoduro, one of the districts of Venice, and dossum oliveti, which will give its name to Olivolo, today’s Castello, another district of Venice).

A freshwater stream, the rivus altus (Rialto), marked the current course of the Grand Canal, on whose banks human settlements had been built since prehistoric times, as well as in the territory of Torcello.

In the basin of San Marco stood a saltern, with the floor in Roman bricks placed more than 3 meters below the current level of the common tide.

According to Titus Livius, the fugitives from the Trojan War came in search of refuge on the Venetian coast and Aeneas founded Venice in 1107 BC. Martino da Canal also describes how the Trojans landed in the area of Olivolo and placed there their first settlement.

One of the first centers built was a port called Metamauco and dates back to Roman times. It stood near today’s Malamocco, in the Lido of Venice, and was located at the mouth of the river Medoacus Maior, the current river Brenta.

Legend has it that it was located further out to sea than the modern Malamocco. A catastrophic climatic event caused it to sink under the sea and it is said that in good weather you can still see its submerged walls and that the fishermen’s nets sometimes remain imprisoned in the tip of the bell tower.

During the last two millennia the activity of tides, winds, coastal currents and the progressive rise in sea level led to a gradual transformation from continent to lagoon, accentuated by the deviation of rivers led to flow into other parts of the coast by man.

Venice begins to see its population grow as a result of the barbarian invasions that followed one another since the fifth century. The fugitives found in the lagoon city protection provided by the Byzantine Empire, present in the territory in different administrative forms.

The growing economic development and the distance from the capital Constantinople were the circumstances that allowed to achieve the administrative autonomy that led to the birth of the Republic of Venice, the Serenissima.

In a short time Venice conquered the political and military hegemony in the Adriatic Sea and throughout the Mediterranean, becoming the main seaport and trading center.

Immediately afterwards, the Serenissima will reach its maximum splendour.

“And if their lagunes are gradually filling up, if unwholesome vapours are floating over the marsh, if their trade is declining, and their power has sunk, still the great place and the essential character will not, for a moment, be less venerable to the observer.”

– Johann Wolfgang Goethe

Sources

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storia_di_Venezia

http://www.viagginellastoria.it/archeoletture/luoghi/1940venezia.htm

https://evenice.it/blog/info/compleanno-di-venezia.html

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martino_Canal

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storia_della_Repubblica_di_Venezia

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repubblica_di_Venezia

James Abbott McNeill Whistler: a true lover of Venice

“If the man who paints only the tree, or the flower, or other surface he sees before him were an artist, the king of artists would be the photographer. It is for the artist to do something beyond this.”

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

James Abbott McNeill Whistler was a great and famous American painter, who became famous for works such as “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1” also known as “Whistler’s Mother”.

What the fewest people know, however, is his genius in the production of chalcographic engravings: Whistler has been one of the most inventive and influential engravers in history, making almost 500 engravings in five decades.

He approached engraving in 1857, at the age of 23, as a gifted and passionate young draughtsman, using the chalcographic technique to capture and reproduce quick sketches at the time when engraving was used as a mere reproductive technique.

From the 18th century onwards, in fact, the art print had become almost exclusively a means of reproducing works of art and portraits, going towards a real industrialisation.

At the end of the 19th century, with the birth and success of photography, engraving was able to free itself of its utilitarian function, thanks to artists such as Whistler, who rediscovered the vitality and autonomy that characterized it at the beginning.

In his first years of experimentation with this technique he worked outdoors, drawing on suitably prepared copper, and then proceeding to morsure in his room, travelling around Alsace-Lorraine and the Rhineland.

In 1859 he moved to London, where he produced views of the Thames, maintaining the purity of unadorned realism inspired by Japanese prints.

At that time he also began to rub the inks in an expressive way and to work using the technique of drypoint, preferring it to etching, for the production of portraits and figures.

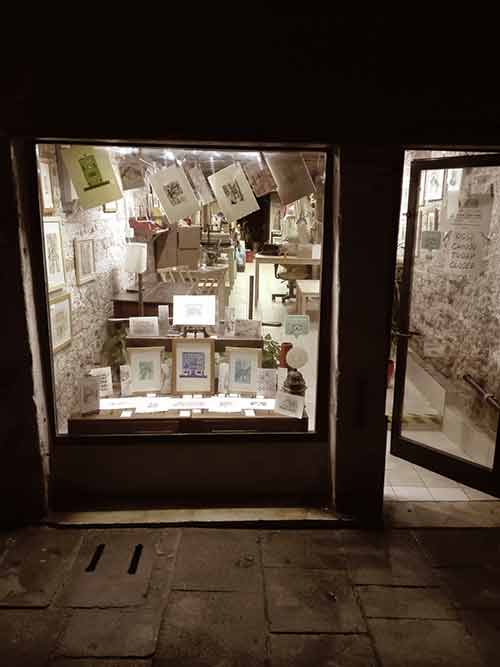

From September 1879 Whistler moved to Venice to produce twelve etchings, commissioned by the Fine Arts Society of London, which expected the return of the artist after a stay of three months.

The artist instead stops in the city for fourteen months and produces fifty etchings, over a hundred pastels, reaching its creative peak.

The views of smaller canals, the entrances to palaces, the reflections dancing on the water and the dark evanescent landscapes represent places known by the locals, far from the tourist routes, just before Venice was sold to the masses

As a supporter of “Art for Art’s sake”, in the celebration of visual beauty, his production is an honest work that shows the most intimate spaces of Venice, showing the viewer the city through the eyes of a Venetian and helps to redraw the map of the city.

Etching gave Whistler the opportunity to combine the speed of execution, quickly drawing ideas on the plate, with the possibility of perfecting and developing them across multiple states, highlighting its complex aesthetics.

His work, with such an innovative approach, has not only attracted followers and imitators, but has also influenced the entire art world.

-

First Venice set -

Upright Venice

“I learned to know a Venice in Venice that the others never seem to have perceived…”

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Sources

https://www.frasicelebri.it/frasi-di/james-mcneill-whistler/ https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Abbott_McNeill_Whistler

https://themitchellgallery.wordpress.com/2013/11/06/james-mcneill-whistler/

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/whet/hd_whet.htm

https://news.virginia.edu/content/museum-opens-printmaking-venice-exhibit-inspired-whistler-s-art

https://plumplumcreations.com/the-history-of-printmaking-part-2/

October, 29th: an ordinary day on an extraordinary high water

Do you see these people? Do you see them well? Good.

These people are idiots.

These people were photographed on November 11st, 2012 in St. Mark’s Square, when the high water in Venice reached 140 centimeters. These people are part of the vast majority of tourists who visit Venice every year thinking that it is not a city with its problems, its inhabitants, its dramas, but an amusement park where everything is “fake”, everything is fun and everything is legitimate because – as you often hear – “I pay to stay here”.

Another consideration: these idiots are bathing in dirty water, because maybe you don’t know it, but part of the sewers in Venice drain into the canals… and I assure you that that water smells like few things in the world!

I don’t want to be controversial with this blogpost: it wants to be simply the chronicle of what happened from my point of view on October 28th, 2018, when the water in Venice reached 160 centimeters (20 centimeters higher than the picture above). And I want to somehow inform people about some aspects of the high water that they may not know or have never thought about.

I would like to try to make many people understand that maybe they don’t know, or maybe they never thought about it, that for most of the people who live and work in Venice, a high water of these proportions is a real drama.

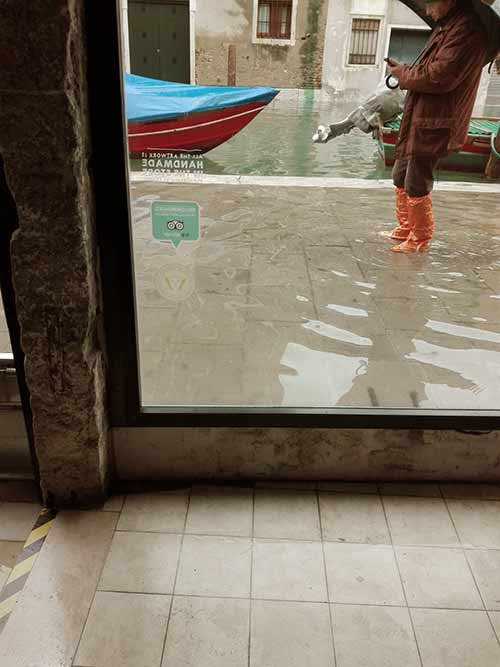

That’s why seeing tourists having fun taking pictures like the one I published above makes me feel angry: because it’s an unconscious mockery of people who suffer serious damage, both economic and even psychological. For example: while I had the shop completely flooded and I was desperately trying to save as much as I could, there were people outside who came by and wanted to take pictures of me.

I don’t think they’re tourists, they’re just jackals.

‘Cause I assure you that seeing your own laboratory, your own shop, your own house invaded by the water is certainly not a pleasure.

I felt awful when I saw that all the measures I had taken to combat this phenomenon had failed.

But first things first.

The high water alarm had begun several days before, when the tide forecast service had announced a very sustained high water for the day 28th in the afternoon. The day before I lifted all the materials that are usually placed on the floor and those that were at a lower level.

One thing has to be taken into account: I have two bulkheads (one for the front door and one for the door to the back yard) and a pump that “spits” out the water when it reaches a certain level and that for the “normal” high waters allows me to stay relatively quiet. The problem, however, is that after a certain measure (around 115 centimeters, so almost every time there is high water!) the high water starts to rise from the floor …! However, for such high waters there are only many annoyances but not real damages.

Below is a photo-story of what happened that day.

The day before I prepared everything: I lifted everything up to protect the materials.

Ocober, 29th: the water starts to grow…

The water level exceeds the shop window and comes dangerously close to the edge of the bulkhead. The water comes from the floor.

At this point it’s really too close, the sirocco wind continues to blow and it’s a moment: the water passes the bulkhead, enters the studio and invades everything. The bulkhead is no longer needed, the pump is no longer needed: there is no longer any difference between inside and outside. Things at a lower level begin to float and go around the store.

Even the courtyard behind was flooded, submerging and ruining my beloved plants that I had unnecessarily placed above some wooden elevations

The tide usually grows for 6 hours and then decreases for the next 6 hours. This time, due to adverse weather conditions (especially the strong sirocco wind), the tide has decreased very little, so that the minimum was around 130 centimeters. And during the evening it came back high again. Luckily then, after midnight, the wind lost strength and the water began to fall, leaving behind only dirt and a very bad smell (…and think that some people take a bath in it!).

The back yard was a disaster too

It took almost three days to clean, disinfect and dry everything. A very hard job, and I realize that I am very lucky because I have not suffered serious damage. There are many shopkeepers and craftsmen with electrical machinery who have suffered irreparable damage, economic damage and now have to start again by investing money: this high water is not fun, it is a misfortune

This testimony of mine does not want to be absolutely a way to out-mourn or self-celebrate: I just want to try to make those who do not know the phenomenon of high water understand what’s really behind something that to many may seem funny, but that actually only involves damage and days of hard work.

I take this opportunity to say hello to all of you who may have learned something from this blogpost and to all the artisans of Venice who do not give up.

Arianna

PS: To take out Bic, my dog who’s always with me in the studio, to do his evening “needs” I had to take him in my arms and find a place high enough where he could walk and not swim… what a feat! And he wasn’t very happy either… 🙂

Linocutting in Venice

A linocut is a type of relief, or block print, very similar to woodblock printing. When you print a linocut, you carve an image into a linoleum (lino) block and what’s left of the block is inked and then it is printed.

I love linocutting so much, and in this blogpost I’d like to share with you the most beautiful part of the process (the last one): the actual printing.

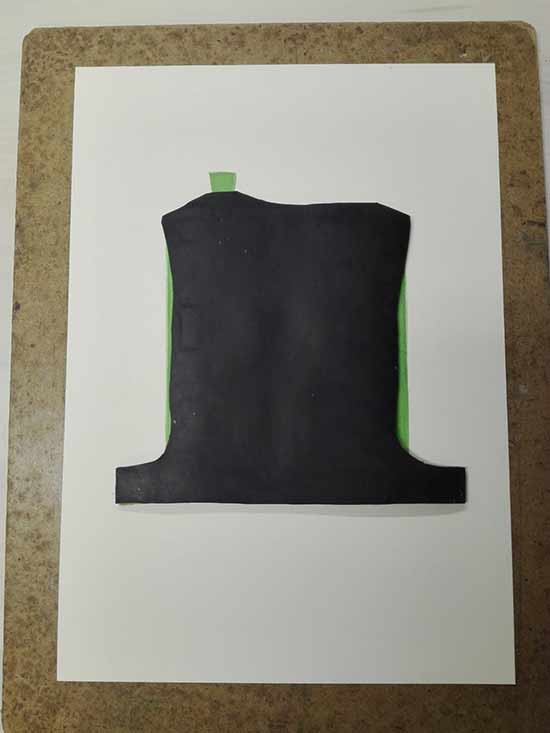

Before printing, I have carved two lino blocks (the most difficult part of the printing process): every block will print a different color on the paper.

When the blocks are ready, I can focus on the preparation of the colors.

The color I have used for the first print was a light green that I created mixing yellow, white and permanent green, a beautiful bright green that needed to be a bit lightened.

I then slightly diluted the ink with vaseline oil, mixing it well with a metal spatula.

I will tell you a little secret: once they are ready, I always keep the colors in a small bag made of cooking paper to preserve them for a long time!

Once I have chosen the color, I have placed it on my inking plane (in plexiglas) with the help of a rubber spatula.

Passing repeatedly on the ink, vertically and horizontally, the roller inks evenly.

I then brought the ink from the roller to the plate, being careful to cover the entire block.

I have placed the sheet on a wooden board, which serves as surface of my press, and above it the inked rubber plate. A tablet equal to the lower one is placed on top of the plate, and finally a soft rubber sheet, to cushion the pressure of the press.

I inserted the “sandwich” in the press and tightened the press for a few seconds.

I remove the pressure and see the result, gently detaching the plate from the sheet.

And this is the result: the first color is done!

Now I proceed with the second color, repeating the same steps but using the second block- of course! 🙂

For the second color I needed a darker green that matched well with the first one.

I mixed the same bright green of the light block with some payne grey, a grey that tends to blue.

And this is the final result

This is the coloring technique I’ve used to print all my linocuts.

If you would like to learn more about linocut technique and you would love to try to make a linocut of your own, you can try one of my workshops: you’ll enjoy it for sure!

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti

In Venice there are no streets but calli (with a few exceptions, as we learned here), and it’s just the same for the squares: if you hear about “square”, you can’t help to refer to St. Mark’s Square, the one and only square in Venice.

All the other areas of the road network that in the rest of the world are called squares, in Venice are called Campi (Fields).

On ancient times the campi, as the term suggests, were covered with grass and used for cultivation, with orchards and fruit trees, and sheeps or horses could be found grazing there.

Only recently the campi have been paved, but there is still a testimony of what the fields should look like on the days of the Serenissima: to see it just visit the Campo di San Pietro di Castello, with its meadows and trees.

San Pietro di Castello

The social meaning of the campo has always been very strong, since Venice is a polycentric city, built on numerous islands that lived a life of their own.

The open space surrounded by houses was a meeting place for the inhabitants, a place where there was a market and overlooked the craft shops.

On the campo there was always a church, with an adjoining cemetery; the function of the campo as a burial place is still indicated in some cases with the presence of an elevated area more than a meter above normal traffic (Napoleon then banned the practice of burial in the campi, moving the cemetery to the current island of San Michele).

Campo San Trovato and the former cemetery

In the larger campi there were also processions and religious events, as well as tournaments and public speeches.

Even in much more recent times, the campo has been (and still is, even if the depopulation of Venice dramatically has its strong impact) the meeting place of children who played mainly football or other games, such as jumping the rope or going on skates.

Campo dei Gesuiti with children playing football

The well was another inevitable figure in every campo, and it was the only source of water for the city, before the construction of the aqueduct.

Fortunately you can still admire many real finely worked wells, even if unused (if you want to learn more about the functioning of the wells, read this article).

The campi often owe their name to the churches that rise (or rised) there, but also to important families who lived there or to trades that were carried out in ancient times.

When the campo is smaller than usual it is referred to it as Campiello (small field), which is often only a widening of the calle or an appendix to a larger field, and it is usually devoid of well and surrounded by houses.

In the campiello social life was even more typical, because it was just the center of a micro district, where the social fabric of the city was interwoven, with gossip, quarrels and the popular chatter of a lively and crowded city. Carlo Goldoni in his comedy “Il campiello” tells just these habits.The importance of the campiello is also testified by the name given to the important literary prize “Il campiello”, one of the most prestigious and well-known Italian literary prizes.

Campiello

Even smaller than the campiello is the Corte (courtyard), which usually has only one entrance through a portico or a street sometimes equipped with a gate. In fact, the corte was considered an extension of the house, where you could find women who, during the summer, sitting next to their door, engaged in housework activities such as cleaning fish and vegetables, sewing and embroidery, and the practice of inserting beads into a thread for the manufacture of necklaces, a typical activity that in dialect is called “impiraperle”.

Corte

Sources

https://venicewiki.org/wiki/Campo

https://www.innvenice.com/Toponomastica-Venezia.htm

https://venipedia.it/it/campi

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campo_(Venezia)

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campiello

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corte_(Venezia)

Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego

In Venice everything is different from the rest of the world, there’s no doubt. Even the streets are not simple ways to transport people and things, but they are opportunities to see magnificent places at every step.

If you are looking for a “Strada” (Street) in Venice, you’ll find only “Strada Nova” (New Street), located in the Cannaregio district, a real city artery. Strada Nova commonly indicates the long route formed by a long series of spacious streets, from the railway station to Campo Ss. Apostoli- actually, only a part of it is the real Strada Nova.

Its construction began at the beginning of the 19th century and continued for almost the entire century, turning a long and winding road into a spacious and full of shops street.

Strada Nova

The other streets in Venice are called “Calli“, from the Latin callis, which means path.

The “calli” can be very narrow or wide, the “Calli larghe” (wide streets) can be dead end streets- in this case they are called “Rami” (branches), when they lead to a dead end “campo” (field) or directly to a house.

Calle

The “Salizade” are “calli” which once were more important, and that’s why they were first paved with masegni (typical stone used just in Venice), while the others were paved with terracotta bricks (or clay) placed in a herringbone pattern (as you can see even today in front of the Church of Madonna dell’Orto).

Salizada

Madonna dell’Orto

The masegni are the classic gray stones that cover almost the entire Venetian public ground, from the first half of the 18th century. This paving is composed of slabs of trachyte, a volcanic stone extracted in the quarries of the Euganean Hills area, near Padua.

Masegni

Another type of street in Venice is the “Ruga” (from the French Rue): it is a street important for commercial business that have always been there since ancient times.

Ruga

Sometimes the need to create spaces on the streets led to bury the canals, turning them into “Rio Terà” (buried canal): the water of the canal often still flows under the road ground.

Rio Terà

The need to build houses forced the Venetians to widen the houses above the street: this is the case of “Sotoporteghi” (underpasses), a sort of “gallery” through the houses, often dark, where you can see the classic wooden beam ceiling that every Venetian house has.

Sotoportego

Even the names of these different kind of “streets” are particular and different: they often refer to the ancient (or present) proximity to a convent or church or crafts that were practiced in a concentrated way, or they get their name from some famous person who used to live around there, but also by ordinary people who became famous for some reason.

And if all these names were not enough, keep in mind one thing: sometimes you can find the same name of a calle in different areas of the city, leading the distracted or superficial visitor to lose his way (or go crazy at all!).

Sources

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strada_Nova

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calle

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti

Venice place names: Campi, Campielli, Corti  Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego

Venice place names: Calle, Calle Larga, Salizada, Rio terà, Ramo, Sotoportego  The Venetian “Fondamenta”

The Venetian “Fondamenta”  2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!

2 years and still going strong: happy birthday Plum Plum Creations!  The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara

The Bicentenary of Gallerie dell’Accademia – Canova, Hayez, Cicognara